Home » Posts tagged 'John F. Kennedy'

Tag Archives: John F. Kennedy

DEMAND-SIDE ECONOMICS VERSUS SUPPLY-SIDE ECONOMICS

June 14, 2018 3:04 am / Leave a comment

On May 9th, 2018, the YouTube Channel, Juice Media uploaded a video entitled “Honest Government Ad: Trickle Down Economics.” In the video, the rather obnoxious and condescending female presenter tells the audience that the reason Australia has “one of the fastest growing inequality rates in the world” is trickle-down economics, which she defines as “when we [the government] piss on you and tell you it’s raining.”

According to the video, tax cuts for investors, entrepreneurs, and business are directly correlated with poverty and the lack of wage growth in Australia. The presenter argues that the government cuts taxes on the rich while simultaneously claiming that they don’t have enough money for healthcare (which would be a lot more effective if people took responsibility for their own health), renewable energy (which is really an excuse to take control of the energy market), and the ABC (which doesn’t deserve a cent of anyone’s money).

The primary problem with the video is that the premise of its argument does not actually exist. There is not a single economic theory that can be identified as trickle-down economics (also known as trickle-down theory). No reputable economist has ever used the term, nor have they ever presented an argument that could be said to conform to the idea of what it is supposed to be. As Thomas Sowell (1930 – ) wrote in his book, Basic Economics:

“There have been many economic theories over the centuries accompanies by controversies among different schools and economists, but one of the most politically prominent economic theories today is one that has never existed among economists: the trickle-down theory. People who are politically committed to policies of redistributing income and who tend to emphasise the conflicts between business and labour rather than their mutual interdependence often accuse those opposed to them of believing that benefits must be given wealthy in general, or to business in particular that these benefits will eventually trickle down to the masses of ordinary people. But no recognised economist of any school of thought has ever had any such theory or made any such proposal.”

The key to understanding why political players disparage pro-capitalist and pro-free market economic policies as trickle-down economics is understanding how economics is used to deceive and manipulate. Political players understand that simple and emotionally-charged arguments tend to be more effective because very few people understand actual economics. Anti-capitalists and anti-free marketeers, therefore, use the term trickle-down economics to disparage economic policy that disproportionately benefits the wealthy in the short term, and increases the standards of living for all peoples in the long-term

The economic theory championed by liberals (read: leftists) is demand-side economics. Classical economics rejected demand-side economic theory for two reasons. First, manipulating demands is futile because demand is the result of product, not its cause. Second, it is (supposedly) impossible to over-produce something. The French economist, Jean-Baptiste Say (1767 – 1832) demonstrated the irrelevance of demand-side economics by pointing out that demand is derived from the supply of goods and services to the market. As a consequence of the works of Jean-Baptiste Say, the British economist, David Ricardo (1772 – 1823), and other classical economists, demand-side economic theory lay dormant for more than a century.

One classical economist, however, was prepared to challenge the classical economic view of demand-side economics. The English economist, Thomas Robert Malthus (1766 – 1834) challenged the anti-demand view of classical economics by arguing that the recession Great Britain experienced in the aftermath Napoleonic Wars (1803 – 1815) was caused by a failure of demand. In other words, purchasing power fell below the number of goods and services in the market. Malthus wrote:

“A nation must certainly have the power of purchasing all that it produces, but I can easily conceive it not to have the will… You have never I think taken sufficiently into consideration the wants and tastes of mankind. It is not merely the proportion of commodities to each other but their proportion to the wants and tastes of mankind that determines prices.”

Using this as his basis, Malthus argued that goods and services on the market could outstrip demand if consumers choose not to spend their money. Malthus believed that while production could increase demand, it was powerless to create the will to consume among individuals.

Demand-side economics works on the theory that economic growth can be stimulated by increasing the demand for goods and services. The American economist, J.D. Foster, the Norman B. Ture Fellow in the Economics of Fiscal Policy at the Heritage Foundation, argued that demand-side works on the theory that the economy is underperforming because the total demand is low, and, as a consequence, the supply needed to meet this demand is likewise low.

The American economist, Paul Krugman (1953 – ), and other economists believe that recessions and depressions are the results of a decrease in demand and that the most effective method of revivifying the economy is to stimulate that demand. The way to do this is to engage in large-scale infrastructure projects such as the building of bridges, railways, and highways. These projects create a greater demand for things like steel, asphalt, and so forth. And, furthermore, it provides people with a wage which they can spend on things like food, housing, clothing, entertainment, so on and so forth.

Policies based on demand-side economics aims to change the aggregate demand in the economy. Aggregate demand is consumer spending + investment + net import/export. Demand-side economics policies are either expansive or contractive. Expansive demand-side policies aim at stimulating spending during a recession. By contrast, contractive demand-side policies aim at reducing expenditure during an inflationary economy.

Demand-side policy can be split into fiscal policy and monetary policy. The purpose of fiscal policy in this regard is to increase aggregate demand. Demand-side based fiscal policy can help close the deflationary gap but is often not sustainable over the long-term and can have the effect of increasing the national debt. When such policies aim at cutting spending and increasing taxes, they tend to be politically unpopular. But when such policies that involve lowering taxes and increasing spending, they tend to be politically popular and therefore easy to execute (of course they never bother to explain where they plan to get the money from).

In terms of monetary policy, expansive demand-side economic aims at increasing aggregate demand while contractive monetary policy in demand-side economics aims at decreasing it. Monetary expansive policies are less efficient because it is less predictable and efficient than contractive policies.

Needless to say, demand-side economics has plenty of critics. According to D.W. McKenzie of the Mises Institute, demand-side economics works on the idea that “there are times when total spending in the economy will not be enough to provide employment to all want to and should be working.” McKenzie argued that the “notion that economics as a whole, sometimes lacks sufficient drive derives from a faulty set of economic doctrines that focus on the demand side of the aggregate economy.” Likewise, Thomas Sowell argued in Supply-Side Politics that there is too much emphasis placed on demand-side economics to the detriment of supply-side economics. He wrote in an article for Forbes:

“If Keynesian economics stressed the supposed benefit of having government manipulate aggregate demand, supply-side economics stressed what the marketplace could accomplish, one it was freed from government control and taxes.”

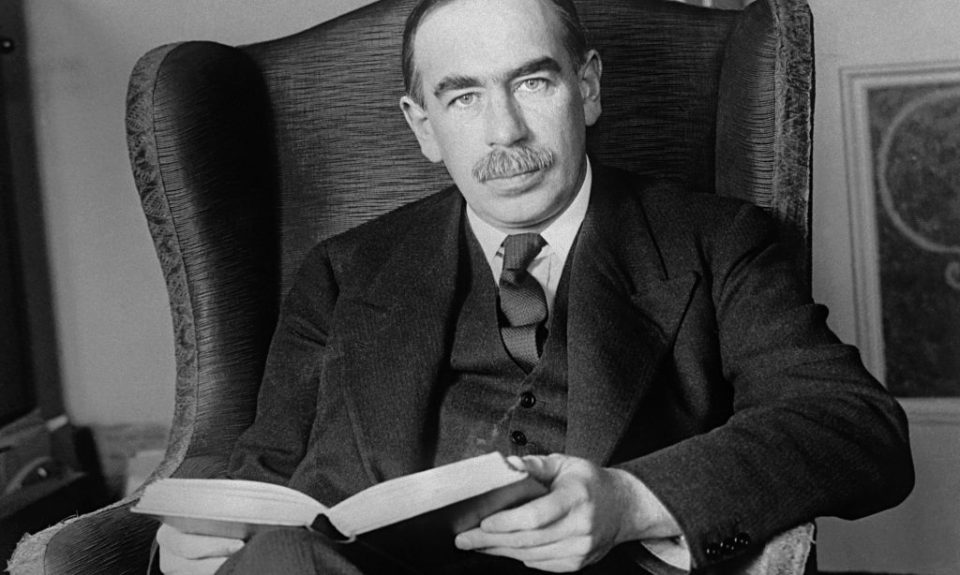

John Maynard Keynes

The man who greatly popularised demand-side economics was the British economist, John Maynard Keynes (1883 – 1946). Keynes, along with many other economists, analysed the arguments of the classical economists against the realities of the Great Depression. Their analysis led many economists to question the arguments of the classical economists. They noted that classical economics failed to answer how financial disasters like the Great Depression could happen.

Keynesian economics challenged the views of the classical economists. In his 1936 book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (one of the foundational texts on the subject of modern macroeconomics) Keynes revivified demand-side economics. According to Keynes, output is determined by the level of aggregate demand. Keynes argued that resources are not scarce in many cases, but that they are underutilised due to a lack of demand. Therefore, an increase in production requires an increase in demand. Keynes’ concluded that when this occurs it is the duty of the government to raise output and total employment by stimulating aggregate demand through fiscal and monetary policy.

The Great Depression is often seen as a failure of capitalism. It popularised Keynesian economics and monetary central planning which, together, “eroded and eventually destroyed the great policy barrier – that is, the old-time religion of balanced budgets – that had kept America relatively peaceful Republic until 1914.”

David Stockman of the Mises Institute argues that the Great Depression was the result of the delayed consequences of the Great War (1914 – 1918) and financial deformations created by modern central banking. However, the view that the Great Depression was a failure of capitalism is not one shared by every economist. The American economist, Milton Friedman (1912 – 2006), for example, argued that the Great Depression was a failure of monetary policy. Friedman pointed out that the total quantity of money in the United States – currency, bank deposits, and so forth – between 1929 and 1933 declined by one-third. He argued that the Federal Reserve had failed to prevent the decline of the quantity of money despite having the power and obligation to do so. According to Friedman, had the Federal Reserve acted to prevent the decline in the quantity of money, the United States (and subsequently, the world) would only have suffered a “garden variety recession” rather than a prolonged economic depression.

It is not possible to determine the exact dimensions of the Great Depression using quantitative data. What is known, however, is that it caused a great deal of misery and despair among the peoples of the world. Failed macroeconomic policies combined with negative shocks caused the economic output of several countries to fall between twenty-five and thirty-percent between 1929 and 1932/33. In America between 1929 and 1933, production in mines, factories, and utilities fell by more than fifty-percent, stock prices collapsed to 1/10th of what they had been prior to the Wall Street crash, real disposable income fell by twenty-eight percent, and unemployment rose from 1.6 to 12.8 million.

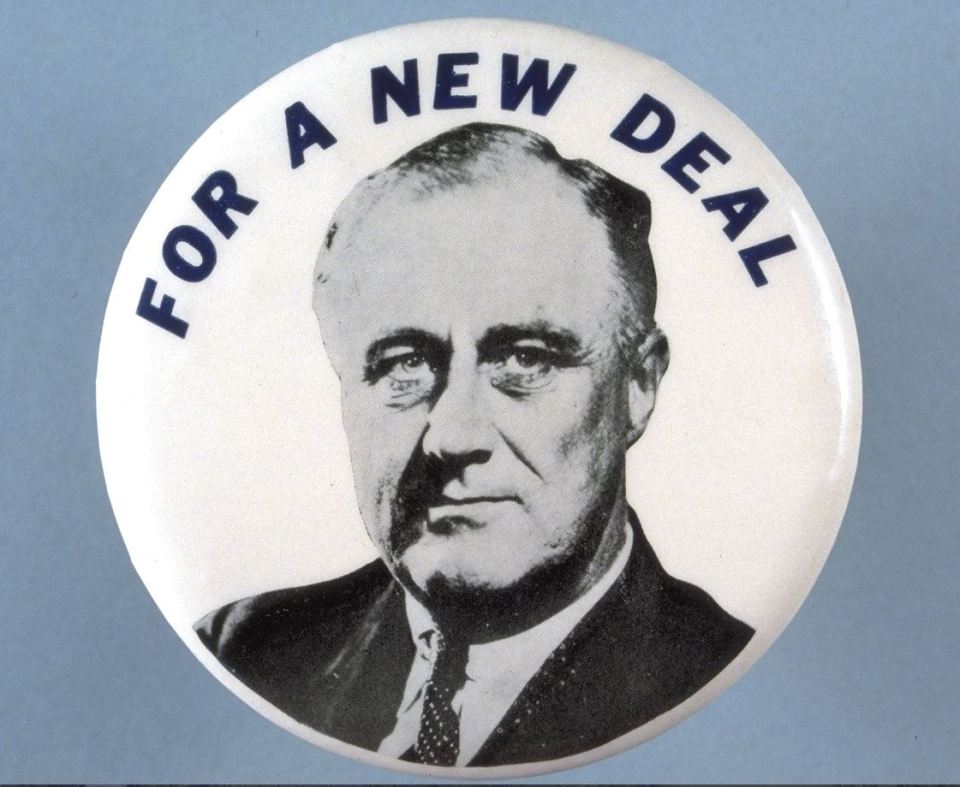

According to an article for the Foundation for Economic Education, What Caused the Great Depression, the Great Depression occurred in three phases. First, the rise of “easy money policies” caused an economic boom followed by a subsequent crash. Second, following the crash, President Herbert Hoover (1874 – 1964) attempted to suppress the self-adjusting aspect of the market by engaging in interventionist policies. This caused a prolonged recession and prevented recovery. Hourly rates dropped by fifty-percent, millions lost their jobs (a reality made worse by the absence of unemployment insurance), prices on agricultural products dropped to their lowest point since the Civil War (1861 – 1865), more than thirty-thousand businesses failed, and hundreds of banks failed. Third, in 1933, the lowest point of the Depression, the newly-elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882 – 1945) combatted the economic crisis by using “new deal” economic policies to expand interventionist measures into almost every facet of the American economy.

Let’s talk about the New Deal a little bit more. The New Deal was the name for the Keynesian-based economic policies that President Roosevelt used to try and end the Great Depression. It included forty-seven Congress-approved programs that abandoned laissez-faire capitalism and enacted the kind of social and economic reforms that Europe had enjoyed for more than a generation. Ultimately, the New Deal aimed to create jobs, provide relief for farmers, boost manufacturing by building partnerships between the private and public sectors, and stabilise the US financial system.

The New Deal was largely inspired by the events of the Great War. During the War, the US Government had managed to increase economic activity by establishing planning boards to set wages and prices. President Roosevelt took this as proof positive that it was government guidance, not private business, that helped grow the economy. However, Roosevelt failed to realise that the increase in economic activity during the Great War came as the result of inflated war demands, not as the achievement of government planning. Roosevelt believed, falsely, that it was better to have government control the economy in times of crisis rather than relying on the market to correct itself.

The New Deal came in three waves. During his first hundred days in office, President Roosevelt approved the Emergency Banking Act, Government Economy Act, the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Federal Emergency Relief Act, Agricultural Adjustment Act, Emergency Farm Mortgage Act, the Tennessee Valley Authority Act, the Security Act, Abrogation of Gold Payment Clause, the Home Owners Refinancing Act, the Glass-Steagall Banking Act, the National Industrial Recovery Act, the Emergency Railroad Transportation Act, and the Civil Works Administration.

In 1934, President Roosevelt bolstered his initial efforts by pushing through the Gold Reserve Act, the National Housing Act, the Securities Exchange Act, and the Federal Communications Act.

In 1935, the Supreme Court rejected the National Industrial Act. President Roosevelt, concerned that other New Deal programs could also be in jeopardy, embarked on a litany of programs that would help the poor, the unemployed, and farmers. Second-wave New Deal programs included Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act, Emergency Relief Appropriation, the Rural Electrification Act, the National Labor Relations Act, the Resettlement Act, and the Social Securities Act.

In 1937, Roosevelt unleashed the third wave of the New Deal by aiming to combat budget deficits. It included the United States Housing Act (Wagner-Steagall), the Bonneville Power Administration, the Farm Tenancy Act, the Farm Security Administration, the Federal National Mortgage, the New Agriculture Adjustment Act, and the Labor Standards Act.

According to the historical consensus, the New Deal proved effective in boosting the American economy. Economic growth increased by 1.8% in 1935, 12.9% in 1936, and 3.3% in 1937. It built schools, roads, hospitals, and more, prevented the collapse of the banking system, reemployed millions, and restored confidence among the American people.

Some even claim that the New Deal didn’t go far enough. Adam Cohen, the author of Nothing to Fear: FDR’s Inner Circle and the Hundred Days that Created Modern America, claims that the longevity of the Depression (the American economy didn’t return to pre-depression prosperity until the 1950s) is evidence that more New Deal spending was needed. Cohen commented that the New Deal had the effect of steadily increasing GDP (gross domestic product) and reducing unemployment. And, which is more, it reimagined the US Federal government as a welfare provider, a stock-market regulator, and a helper of people in financial difficulty.

However, the historical consensus is not to say that the New Deal is without its critics. The New Deal was criticised by many conservative businessmen for being too socialist. Others, such as Huey Long (1893 – 1935), criticised it for failing to do enough for the poor. Henry Morgenthau, Jr. (1891 – 1967), the Secretary of the Treasury, confessed before Democrats in the House Ways and Means Committee on May 9th, 1939 that the New Deal had failed as public policy. According to Morgenthau, it failed to produce an economic recovery and did not erase historic unemployment. Instead, it created a recession – the Roosevelt Recession – in 1937, failed to adequately combat unemployment because it created jobs that were only temporary, became the costliest government program in US history, and wasted money.

Conservatives offer supply-side economics as an alternative to demand-side economics. Supply-side economics aims at increasing aggregate supply. According to supply-side economics, the best way to stimulate economic growth or recovery is to lower taxes and thus increase the supply of goods and services. This increase leads, in turn, to lower prices and higher standards of living.

The lower-taxes policy has proved quite popular with politicians. The American businessman and industrialist, Andrew Mellon (1855 – 1937) argued for lower taxes in the 1920s, President John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1917 – 1963) argued for lower taxes in the 1960s, and both President Ronald Reagan (1911 – 2004) and President George Walker Bush (1946 – ) lowered taxes in the 1980s and 2000s, respectively.

Supply-side economics works on the principle that producers will create new and better products if they are allowed to keep their money. Put simply, supply-side economics (supply merely refers to the production of goods and services) works on the theory that cutting taxes on entrepreneurs, investors, and business-people incentives them to invest more in their endeavours. This money can be invested in capital – industrial machinery, factories, software, office buildings, and so forth.

The idea that lower taxes lead to greater economic prosperity is one of the central tenants of supply-side economics. Supporters of supply-side economics believe that providing financial benefits for investors (cutting capital gains tax, for example) stimulates economic growth. By contrast, high taxes, especially those metered out on businesses, discourage investment and encourages stagnation.

Tax rates and tax revenue are not the same thing, they can move in opposite directions depending on economic factors. The revenue collected from income tax for each year of the Reagan Presidency was higher than the revenues collected during any year of any previous Presidency. It can be argued that people change their economic behaviour according to the way they are taxed. The problem with increasing taxes on the rich is that the rich will use legal, and sometimes illegal, strategies for avoiding paying it. A businessman who is forced to pay forty-percent of his business’ profits on taxation is less likely to increase his productivity. As a consequence, high tax rates on businesses leads to economic stagnation.

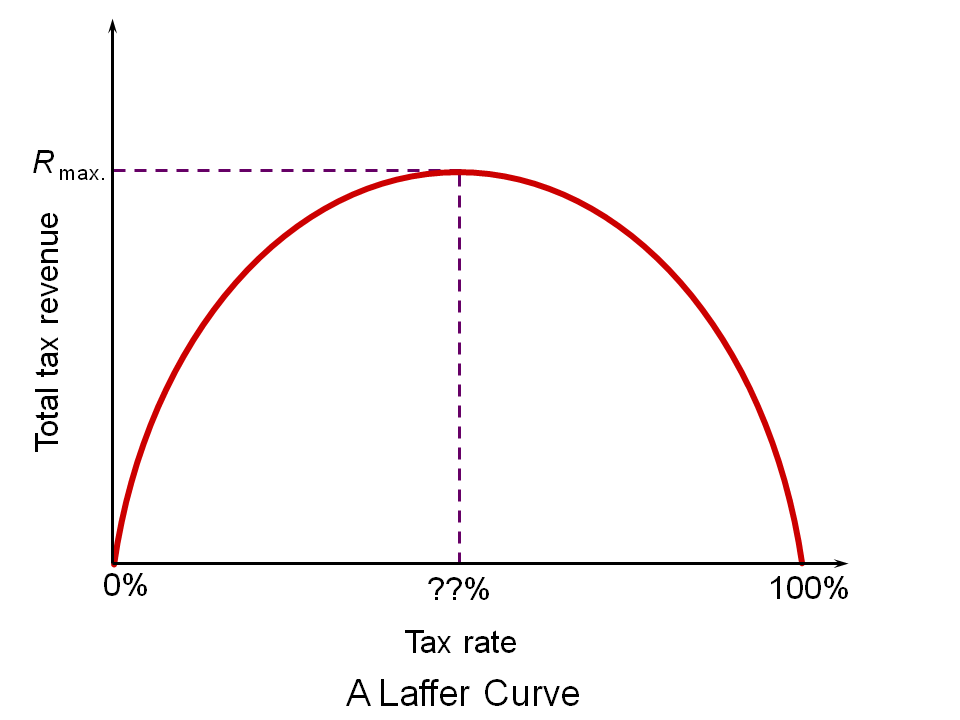

Supply-side supporters use Arthur Laffer’s (1940 – ) – an advisor to President Ronald Regan – Laffer Curve to argue that lower taxes lead to higher tax revenue. The Laffer curve showed the dichotomy between tax revenue and the amount of tax that is collected. Laffer’s idea that the more taxation increased, the more tax revenue is collected. However, if taxes are increased beyond a certain point, less revenue is collected because people are no longer willing to make an economic contribution.

Taxation only works when the price of engaging in productive behaviour is likewise reduced. Daniel Mitchell of the Heritage Foundation stated in an article entitled a “Supply-Side” Success Story, that tax cuts are not created equally. Mitchell wrote: “Tax cuts based on the Keynesian notion of putting money in people’s pockets in the form of rebates and credits do not work. Supply-side cuts, by contrast, do improve economic performance because they reduce tax rates on work, saving, and investment.” Mitchell used the differences between the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts as evidence for his argument. Mitchell pointed out that tax collections fell after the 2001 tax cuts whereas they grew by six-percent annually after the 2003 cuts. Mitchell points out that job numbers declined after the 2001 cuts whereas net job creation averaged more than 150,000 after the 2003 cuts. Mitchell points out that economic growth averaged 1.9% after the 2001 tax cuts, compared to 4.4% after the 2003 cuts.

Proposals to cut taxes have always been characterised by its opponents as “tax cuts for the rich.” The left believes that tax cuts, especially cuts on the top rate of tax, does not spur economic growth for lower and middle-class people and only serves to widen income inequality. They argue that tax cuts benefit the wealthy because they invest their newfound money in enterprises that benefit themselves. Bernie Sanders (1941 – ), the Independent Senator from Vermont, has argued that “trickle-down economics” is pushed by lobbyists and corporations to expand the wealth of the rich. Whilst opponents of President Ronal Reagan’s tax cuts likewise referred to the policy as “trickle-down economics.”

In reality, the left-wing slander of tax cuts can best be described as “tax lies for the gullible.” The rich do not become wealthy by spending frivolously or by hiding their money under the mattress. The rich become rich because they are prepared to invest their money in new products and ventures that will generate greater wealth. In reality, it is far more prudent to give an investor, entrepreneur, or business owner a tax cut because they are more likely to use their newfound wealth more prudently.

According to Prateek Agarwal at Intelligent Economist, supply-side economics is useful for lowering the natural rate of unemployment. Thomas Sowell, a supporter of supply-side economics, claims that while tax cuts are applied primarily to the wealthy, it is the working and middle classes who are the first and primary beneficiaries. This occurs because the wealthy, in Sowell’s view, are more likely to invest more money in their businesses which will provide jobs for the working class.

The purpose of economic policy is to facilitate the economic independence of their citizens by encouraging economic prosperity. Demand-side economics and supply-side economics represent two different approaches to achieving this endeavour. Demand-side economics argues that economic prosperity can be achieved by having the government increase demand by taking control of the economy. By contrast, supply-side economics, which is falsely denounced as “trickle-down economics” by the likes of people like Juice Media, champions the idea that the best way to achieve economic prosperity is by withdrawing, as far as humanly possible, government interference from the private sector of the economy. Supply-side economics is the economic philosophy of freedom, demand-side economics is not.

NAPOLEON SYNDROME

October 25, 2017 4:49 am / Leave a comment

Shorter men who attempt to assert or defend themselves are frequently met with the harrowing accusation that they are suffering from ‘Napoleon complex’, otherwise known as ‘short man syndrome.’ While there is some evidence – based both on research and common experience – that this may be the case, the root causes of the issue reveal a problem that is more complex and entrenched than the general public would like to believe.

The term ‘Napoleon complex’ was first coined by Alfred Adler (1870 – 1937) in 1912. Remarkably, however, Napoleon Bonaparte (1769 – 1821), the man for whom ‘Napoleon syndrome’ is named, was not actually short. Napoleon’s personal physician, Francesco Antommarchi (1780 – 1838), recorded the deposed Emperor’s height as being five pieds, two pouces, or five-feet, six-and-a-half inches. This was a half-inch taller than the average Englishman of the time, and a full two inches taller than the average Frenchman. The myth of Napoleon’s short stature comes from two places. First is the fact that Napoleon frequently surrounded himself with men taller than himself. Height requirements specified that the Grenadiers in the Elite Imperial Guard be 5’10 or over, whilst members of the Mounted Chasseurs had to be 5’7. To any casual observer, Napoleon would have looked noticeably smaller by comparison. And second, there is the anti-Napoleonic propaganda that frequently depicted the Emperor as small.

Like many physical characteristics, height can have a profound effect on a person’s self-perception. The shorter man’s poor self-perception begins in childhood when smaller children are often the targets of taunts and ridicule. As adults, shorter men are more likely to be overly-aggressive, domineering, and have an increased proclivity for resorting to extreme measures in order to prove themselves. Unfortunately, research shows that shorter men may, in extreme cases, resort to violence as a means of disguising their insecurities. The Journal of Injury Prevention found that men who struggled with their height and masculinity were three times more likely to commit violent assaults using a weapon. This study, which involved six-hundred American men aged between eighteen and fifty, asked participants to answer two sets of questions. The first asked about their self-image, drug use, and violent behaviour. The second set of questions asked the participants about their beliefs on gender roles, how they felt women and their friends perceived them, how they perceived their own masculinity, and how much they’d like to be a “macho man.”

Taller men are far more likely to succeed in positions of authority and power than shorter men. An early study of height and occupation reveals bishops to be taller than parish priests, sales managers to be taller than salesmen, and university presidents to be taller than the presidents of more modest higher-education facilities. In US Presidential elections, it is typically the taller of the two Presidential candidates that end up winning: John F. Kennedy (1917 – 1963) was six-feet tall compared to Richard Nixon (1913 – 1994) who was five-foot-eleven, Ronald Reagan (1911 – 2004) was six-foot-one compared to Jimmy Carter (1924 – ) who was five-foot-ten, and Barack Obama (1961 – ) was six-foot-one compared to John McCain’s (1936 – ) who was five-foot-nine.

And, as if that isn’t bad enough, merely finding employment can be a struggle for many shorter men. A 2001 study by Nicolo Persico, Andrew Postlewaite, and Dan Silverman of the University of Pennsylvania, found that shorter teenagers had a harder time finding employment than their taller counterparts. Persico, Postlewaite, and Silverman chalked this up to the attitudes and worldview of the shorter teenager. “Those who were relatively short when young”, they explained, “were less likely to participate in social activities associated with the accumulation of productive skills and attributes, and report lower self-esteem.”.

Things don’t get much better once they are employed, either. Shorter men are less likely to be afforded promotions and pay-rises than their taller peers. A study by Leland Deck of the University of Pittsburgh found that men who are 6’2 or taller earn 12.4% more than men who are below six feet.

Then there is the challenge of forming intimate relationships. Men are considered attractive when they are tall, broad-shouldered, and well-toned. An analysis of personal ads found that most women prefer dating men who are six-foot-tall and over, especially when it comes to casual sex. A study published in the March 2016 edition of Personality and Individual Differences journal found that while women did not particularly care about hair, weight, or penis size, they did care about a man’s height. It is believed that the primary reason for this preference is that height is a sign of high testosterone – and men with higher testosterone tend to be better protectors and lovers.

There is plenty of evidence to suggest that height is a source of great insecurity for many men. The shorter man’s sense of insecurity and resentment is almost certainly borne out of poor experiences associated with their stature. Smaller children are more likely to be the victims of taunts and ridicule. As adults, shorter men find it more difficult to form intimate relationships, find employment, and achieve positions of authority and status. Perhaps people ought to remember that Napoleon Complex is more complicated and entrenched than they like to believe.

CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS

October 11, 2017 6:18 am / Leave a comment

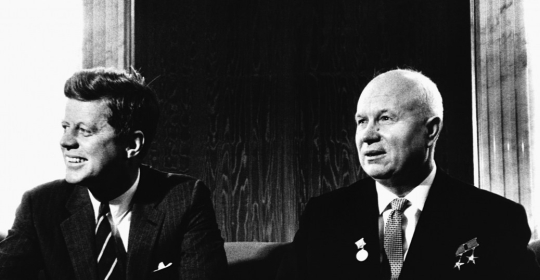

Next Monday will mark fifty-five years since the Cuban Missile Crisis. For thirteen days, the world held its collective breath as tensions between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics reached boiling point. Whoever averted the crisis would be glorified in the annals of history, whoever escalated it would be responsible for the annihilation of life on earth.

Our story begins in July, 1962, when Cuban dictator Fidel Castro (1926 – 2016) and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev (1894 – 1971) came to a secret agreement to deter another US-backed invasion attempt (the US had previously backed the disastrous Bay of Pigs operation, and were planning another invasion called ‘Operation Mongoose’) by planting nuclear missiles on Cuban soil. On September 4th, routine surveillance flights discovered the general build-up of Soviet arms, including Soviet IL-28 bombers. President John F. Kennedy (1917 – 1963) issued a public warning against the introduction of offensive weapons in Cuba.

Another surveillance flight on October 14th discovered the existence of medium-range and immediate range ballistic nuclear weapons in Cuba. President Kennedy met with his advisors to discuss options and direct a course of action. Opinions seemed to be divided between sending strong warnings to Cuba and the Soviet Union and using airstrikes to eliminate the threat followed by an immediate invasion. Kennedy chose a third option. He would use the navy to ‘quarantine Cuba’ – a word used to legally distinguish the action from a blockade (an act of war).

Kennedy then sent a letter to Khrushchev stating that the US would not tolerate offensive weapons in Cuba and demanded the immediate dismantling of the sites and the return of the missiles to the Soviet Union. Finally, Kennedy appeared on national television to explain the crisis and its potential global consequences to the American people. Directly echoing the Monroe doctrine, he told the American people: “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” The Joint Chief of Staff then declared a military readiness level of DEFCON 3.

Kennedy then sent a letter to Khrushchev stating that the US would not tolerate offensive weapons in Cuba and demanded the immediate dismantling of the sites and the return of the missiles to the Soviet Union. Finally, Kennedy appeared on national television to explain the crisis and its potential global consequences to the American people. Directly echoing the Monroe doctrine, he told the American people: “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” The Joint Chief of Staff then declared a military readiness level of DEFCON 3.

On October 23rd, Khrushchev replied to Kennedy’s letter claiming that the quarantining of Cuba was an act of aggression and that he had ordered Soviet ships to proceed to the island. When another US reconnaissance flight reported that the Cuban missile sites were nearing operational readiness, the Joint Chiefs of Staff responded by upgrading military readiness to DEFCON 2. War involving Strategic Air Command was imminent.

On October 26th, Kennedy complained to his advisors that it appeared only military action could remove the missiles from Cuba. Nevertheless, he continued to pursue a diplomatic resolution. That afternoon, ABC News correspondent, John Scali (1918 – 1995), informed the White House that he had been approached by a Soviet agent who had suggested that the Soviets were prepared to remove their missiles from Cuba if the US promised not to proceed with an invasion. The White House scrambled to determine the validity of this offer. Later that evening, Khrushchev sent Kennedy a long, emotional message which raised the spectre of nuclear holocaust and suggested a resolution similar to that of the Soviet agent: “if there is no intention to doom the world to the catastrophe of thermonuclear war, then let us not only relax the forces pulling on the ends of the rope, let us take measures to untie the knot. We are ready for this.”

Hope was short-lived. The next day Khrushchev sent Kennedy another message demanding the US remove its Jupiter missiles from Turkey as a part of any resolution. That same day, a U2 Spy Plane was shot down over Cuba.

Kennedy and his advisors now planned for an immediate invasion of Cuba. Nevertheless, slim hopes for a diplomatic resolution remained. It was decided to respond the Khrushchev’s first message. In his message, Kennedy suggested possible steps towards the removal of the missiles from Cuba, suggested the whole business take place under UN supervision, and promised the US would not invade Cuba. Meanwhile, Attorney General Robert Kennedy (1925 – 1968) met secretly with the Soviet Ambassador to America, Anatoly Dobrynin (1919 – 2010). Attorney General Kennedy indicated that the US was prepared to remove its Jupiter missiles from Turkey but that it could not be part of any public resolution.

On the morning of October 28th, Khrushchev issued a public statement. The Soviet missiles stationed in Cuba would be dismantled and returned to the Soviet Union. The United States continued its quarantine of Cuba until the missiles had been removed, and withdrew its Navy on November 20th. In April 1963, the US removed its Jupiter missiles from Turkey. The world breathed a sigh of relief.

The Cuban Missile Crisis symbolises both the terrifying spectre of nuclear holocaust, and the power of diplomacy in resolving differences. By forming an intolerable situation, the presence of nuclear weapons forced Kennedy and Khrushchev to favour diplomatic, rather than militaristic, resolutions. In the final conclusion, it must be acknowledged that nuclear weapons, and the knowledge and technology to produce them, will always exist. The answer, therefore, cannot be to rid the world of nuclear weapons but learn to live peacefully in a world that has them.