Home » Posts tagged 'dictator of Cuba'

Tag Archives: dictator of Cuba

CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS

October 11, 2017 6:18 am / Leave a comment

Next Monday will mark fifty-five years since the Cuban Missile Crisis. For thirteen days, the world held its collective breath as tensions between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics reached boiling point. Whoever averted the crisis would be glorified in the annals of history, whoever escalated it would be responsible for the annihilation of life on earth.

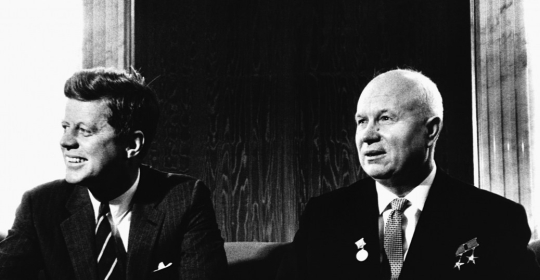

Our story begins in July, 1962, when Cuban dictator Fidel Castro (1926 – 2016) and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev (1894 – 1971) came to a secret agreement to deter another US-backed invasion attempt (the US had previously backed the disastrous Bay of Pigs operation, and were planning another invasion called ‘Operation Mongoose’) by planting nuclear missiles on Cuban soil. On September 4th, routine surveillance flights discovered the general build-up of Soviet arms, including Soviet IL-28 bombers. President John F. Kennedy (1917 – 1963) issued a public warning against the introduction of offensive weapons in Cuba.

Another surveillance flight on October 14th discovered the existence of medium-range and immediate range ballistic nuclear weapons in Cuba. President Kennedy met with his advisors to discuss options and direct a course of action. Opinions seemed to be divided between sending strong warnings to Cuba and the Soviet Union and using airstrikes to eliminate the threat followed by an immediate invasion. Kennedy chose a third option. He would use the navy to ‘quarantine Cuba’ – a word used to legally distinguish the action from a blockade (an act of war).

Kennedy then sent a letter to Khrushchev stating that the US would not tolerate offensive weapons in Cuba and demanded the immediate dismantling of the sites and the return of the missiles to the Soviet Union. Finally, Kennedy appeared on national television to explain the crisis and its potential global consequences to the American people. Directly echoing the Monroe doctrine, he told the American people: “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” The Joint Chief of Staff then declared a military readiness level of DEFCON 3.

Kennedy then sent a letter to Khrushchev stating that the US would not tolerate offensive weapons in Cuba and demanded the immediate dismantling of the sites and the return of the missiles to the Soviet Union. Finally, Kennedy appeared on national television to explain the crisis and its potential global consequences to the American people. Directly echoing the Monroe doctrine, he told the American people: “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” The Joint Chief of Staff then declared a military readiness level of DEFCON 3.

On October 23rd, Khrushchev replied to Kennedy’s letter claiming that the quarantining of Cuba was an act of aggression and that he had ordered Soviet ships to proceed to the island. When another US reconnaissance flight reported that the Cuban missile sites were nearing operational readiness, the Joint Chiefs of Staff responded by upgrading military readiness to DEFCON 2. War involving Strategic Air Command was imminent.

On October 26th, Kennedy complained to his advisors that it appeared only military action could remove the missiles from Cuba. Nevertheless, he continued to pursue a diplomatic resolution. That afternoon, ABC News correspondent, John Scali (1918 – 1995), informed the White House that he had been approached by a Soviet agent who had suggested that the Soviets were prepared to remove their missiles from Cuba if the US promised not to proceed with an invasion. The White House scrambled to determine the validity of this offer. Later that evening, Khrushchev sent Kennedy a long, emotional message which raised the spectre of nuclear holocaust and suggested a resolution similar to that of the Soviet agent: “if there is no intention to doom the world to the catastrophe of thermonuclear war, then let us not only relax the forces pulling on the ends of the rope, let us take measures to untie the knot. We are ready for this.”

Hope was short-lived. The next day Khrushchev sent Kennedy another message demanding the US remove its Jupiter missiles from Turkey as a part of any resolution. That same day, a U2 Spy Plane was shot down over Cuba.

Kennedy and his advisors now planned for an immediate invasion of Cuba. Nevertheless, slim hopes for a diplomatic resolution remained. It was decided to respond the Khrushchev’s first message. In his message, Kennedy suggested possible steps towards the removal of the missiles from Cuba, suggested the whole business take place under UN supervision, and promised the US would not invade Cuba. Meanwhile, Attorney General Robert Kennedy (1925 – 1968) met secretly with the Soviet Ambassador to America, Anatoly Dobrynin (1919 – 2010). Attorney General Kennedy indicated that the US was prepared to remove its Jupiter missiles from Turkey but that it could not be part of any public resolution.

On the morning of October 28th, Khrushchev issued a public statement. The Soviet missiles stationed in Cuba would be dismantled and returned to the Soviet Union. The United States continued its quarantine of Cuba until the missiles had been removed, and withdrew its Navy on November 20th. In April 1963, the US removed its Jupiter missiles from Turkey. The world breathed a sigh of relief.

The Cuban Missile Crisis symbolises both the terrifying spectre of nuclear holocaust, and the power of diplomacy in resolving differences. By forming an intolerable situation, the presence of nuclear weapons forced Kennedy and Khrushchev to favour diplomatic, rather than militaristic, resolutions. In the final conclusion, it must be acknowledged that nuclear weapons, and the knowledge and technology to produce them, will always exist. The answer, therefore, cannot be to rid the world of nuclear weapons but learn to live peacefully in a world that has them.